Formerly temporary, now persistent work-from-home turns into slow-motion nightmare for office landlords.

Authored by Wolf Richter at WOLF STREET

It has been nearly 18 months that many big-company offices became no-go places, and the temporary disruption that was supposed to last only a few months has been dragging on and on. The vaunted and repeatedly delayed “return to the office” – as flexible, partial, and “hybrid” as it was supposed to be – is being pushed out further into next year. February 2022 will close the second year of this shift to working from home.

Apple, which spent a massive fortune on its new campus in Cupertino and wants its people back in it badly, said that it would delay the return to the office until at least January 2022. Amazon, DoorDash, Lyft, Chevron, Wells Fargo, Facebook, and many others have delayed their return to the office until next year as well.

This is on top of the numerous companies that have moved to permanent work-from-home models.

The temporary situation is now becoming ingrained. Routines have formed around it, and people and companies have gotten used to it and found solutions to the problems that arose from it. They discovered the benefits and cost reductions and productivity gains that came with it.

The longer this goes on, the less likely is any return to the old pre-pandemic normal, even as some bosses dread the possibility that the old way of managing people and valuing work may become obsolete.

But all that can be worked out. What can’t be worked out is corporate demand for office space, which has been sagging and pressuring the office sector of commercial real estate.

These companies aren’t going to default on their office leases and mail the keys to the landlord. That’s not the issue. They will continue to make their rent payments.

The issue is that these companies have put vast and historic amounts of office space that they lease but don’t need on the sublease market, trying to find tenants for it, and this sublease space comes on top of the space the landlords are trying to find tenants for. But when lease renewal comes, many of these companies won’t renew, and then it’s the landlord’s job to find new tenants.

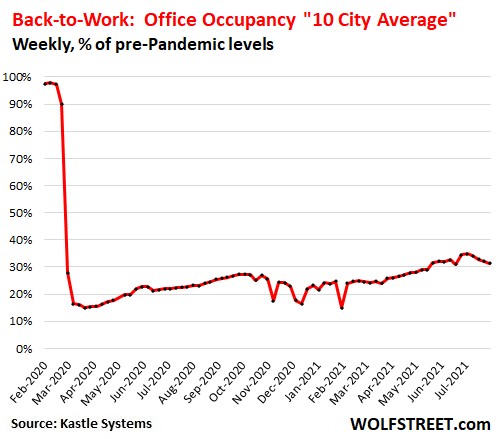

Office occupancy, as measured by workers actually showing up at the office has fallen for the fourth week in a row, from already dreadfully low levels. Kastle Systems, which provides electronic access systems for office buildings, said today that across the 10 cities it tracks, office occupancy in the week through August 18 had dropped to 31.3% of the level before the pandemic (early March 2020), meaning that occupancy was down by 68.7%:

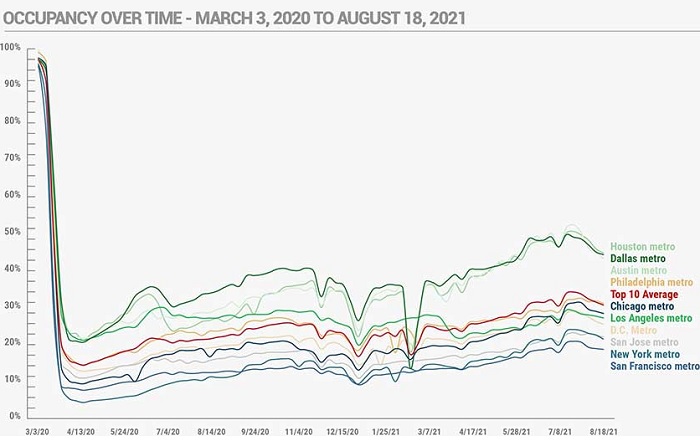

Office occupancy fell in all 10 metros, but fell by the most in the metros that had made the most progress with their return to the office earlier this year: Austin, Dallas, and Houston. Those three metros had already bumped into the 50% line, but now amid the resurgence of the virus in those cities, had dropped to the 45% range, which is still far higher than in the remaining seven cities.

Office occupancy in the metros of San Francisco and San Jose, which is most of the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, and in New York City dropped to the 19% to 22% range, meaning office occupancy is down roughly 80%. These metros are among the most expensive office markets in the US, and they have turned into epicenters for working from home:

Survey after survey has shown that working from home has become very popular among workers, and that it has become more popular the longer it dragged on, and that many people are willing to take a pay cut if that’s what it takes to keep working from home.

People have organized their lives around it, have bought houses to accommodate two offices, have eliminated the endless and stressful hours of commuting, and the expense of it, and they no longer get slowed down by office chatter and sundry annoyances, distractions, and worthless meetings, and they can get their job done faster, and sometimes better. And some of them have even used the extra time they’re saving to pursue a side gig.

And the benefits of working in an office, the camaraderie, if any, the possibilities (fraught with risks) of finding a date or a mate at the corporate coffee bar, the free gourmet lunches at some companies – all this is receding into the background.

The longer this goes on, the less likely people are willing to go back to the office five days a week, and the idea of going to the office two or three days a week may already be a stretch.

This is a red-hot job market, with “labor shortages” written all over it, and with recruiters aggressively plying their trade trying to lure employees away from one company and send them to another.

Employers are going to have to bend over backwards to attract and retain their biggest assets – productive employees – and they’re having to make room for what employees have gotten used to and have structured their lives around: Flexibility about working from home. This isn’t going to get suddenly undone next February.

Some bosses are having a hard time with it, and have little enthusiasm for remote work, and they want their people back at their desks where they can be seen and monitored and “managed.” But in a hot labor market, they don’t have the final say in this. The employee does.

For landlords in the office sector of commercial real estate, this may be the end of the era of voracious appetite by businesses for office space.

Office markets, it now turns out, have been hugely overbuilt. Companies have for years leased office space, or even purchased and built office space, that they thought they might grow into some years down the road, but they never actually grew into it, and they were just warehousing empty office space for future use that now isn’t coming, or may be coming to a much smaller extent.

Sure, some companies will sign new leases to expand their office footprint, and new companies are popping up that rent office space, which is now getting a lot cheaper in places like San Francisco. And there will be many renewals, and some of those renewals, as we have already seen, will be for less space.

But the net effect is that there are vast amounts of unused office space out there. The latest and greatest office buildings will have little trouble filling their space if the rent is low enough, amid a flight to quality, though those lower rents might not have been planned for.

Over time, as long-term commercial leases expire, and as companies are upgrading their digs, the vacancies shift to older buildings.

That is already happening in Houston, the worst office market in the US, where the oil bust that started in late 2014 popped the magnificent office bubble. New fancy buildings have come on the market since then, and landlords are luring tenants away from older buildings, as vacancies have skyrocketed to 31% of total office space.

San Francisco is catching up with Houston, after having been one of the hottest office markets in the US through 2018. It takes years for this to wash out, timed with the expirations of long-term commercial leases, giving cities some time to think about alternatives for the vast amounts of aging and now unneeded office space.